For additional resources, see the Kohl’s Art Generation Online Lab & Gallery guide.

Learn seven tricks that artists use to give the illusion that things in a work of art are near or far. With each trick, we show you two works of art. We compare a work by a more traditional artist with one by an artist who tries to mix it up. Both create spaces that make us question and pay attention to what we are seeing.

Size

Objects far away appear smaller than objects close up. Experience teaches us this. For example, as a car drives away, it becomes smaller and smaller. We interpret this as the car getting farther and farther away. We are familiar with many objects. If an object appears smaller or larger than we know it to be, we can determine whether the object is near or far. This is called “relative size.” Artists use this device when painting an image. The smaller the object, the farther away it seems.

You can experiment with size by creating a stop-motion animation using this free app. You can use real objects and place them farther and farther away from your iOS device, or draw the same object in three different sizes, cut the drawings out, and then animate them. How else can you make animations that show objects moving closer and farther, becoming larger and smaller? (One suggestion: try making your own flipbook!)

Mr. and Mrs. Elliott Ogden M1958.7.

Lynde Bradley M1977.71. Photo credit: John R. Glembin. ©2010 Milton Avery Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New

York

Aerial Perspective

The relative color of objects provides clues as to their distance. Because blue light is not absorbed and scatters in the atmosphere, distant objects, such as mountains, appear bluer. The crispness of an object’s outline also provides clues as to its distance. The scattering of light blurs the outlines of objects, so objects with fuzzy edges are perceived as distant.

Harry Lynde Bradley M1959.377. Photo credit: Dedra Walls. ©2010 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP,

Paris

Milwaukee Art Museum, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Donald B. Abert and Mrs. Barbara Abert Tooman M1974.230. Photo credit:

John Nienhuis

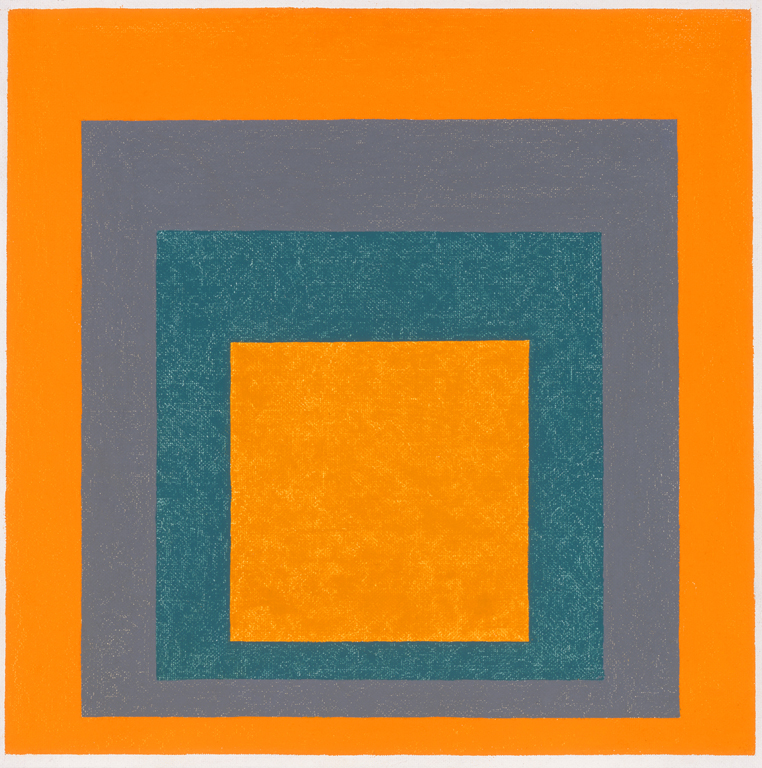

Linear Perspective

Parallel lines that converge to a fixed point create the illusion of depth. A painting that is made using linear perspective might have implied lines, as though the image were “built” over a grid, or lines as obvious as those of a railroad track.

Make your own linear perspective scene: Download this PDF Sketchbook and give it a try!

Rev. Nazarenus Graziani American, active 19th century, Church of the Assumption (The Pink Cathedral), 1885. Oil on canvas. Milwaukee Art Museum, The Michael and Julie Hall Collection of American Folk Art M1989.204. Photo credit: John Nienhuis

Masonite. Milwaukee Art Museum, gift of Anni Albers and the Josef Albers Foundation, Inc. M1981.76. Photo credit:

John R. Glembin. © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Overlapping

When objects overlap, our brains interpret this as one object being in front of another in space.

Museum, Layton Art Collection, Purchase, L1960.1. Photo credit: John R. Glembin

Museum, Maurice and Esther Leah Ritz Collection M2004.128. Photo credit: Efraim Lev-er

Color

Colors can be identified as either warm or cool. Warm colors—reds, oranges, and yellows—tend to appear closer than cool colors—greens, blues, and violets.

Milwaukee Art Museum, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Donald B. Abert and Mrs. Barbara Abert Tooman M1974.230. Photo credit: John Nienhuis

Compare to: Mark Rothko, Green, Red, Blue, 1955

Objects placed near the horizon line appear farther away than those placed below it. Decreasing the size of the object near the horizon line makes the object look even farther away.

funds from the Linda and Daniel Bader Foundation, Suzanne and Richard Pieper, and Barbara Stein M2010.17. Photo

credit: John R. Glembin

Highlights and shadows affect how the eye reads an object’s dimensions and depth. Light that comes from a direction other than above tricks our brains into seeing an object differently than its actual physical form; it becomes distorted.

Milwaukee Art Museum, Gift of Friends of Art and Purchase, M1980.2. Photographer credit: P. Richard Eells